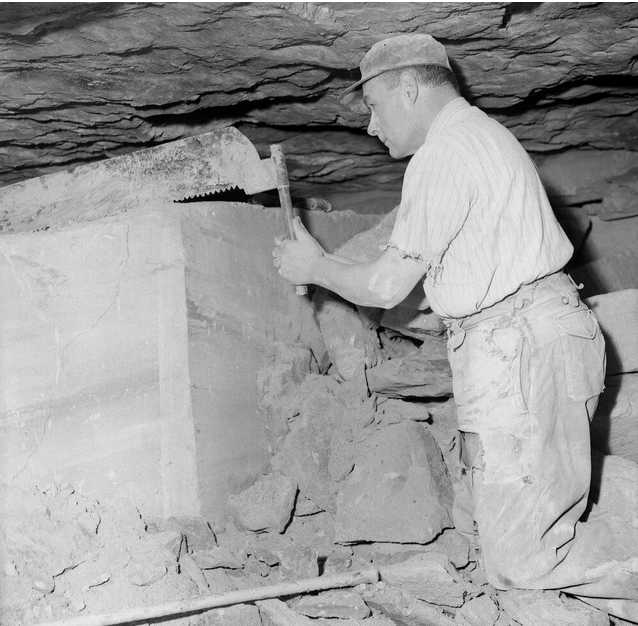

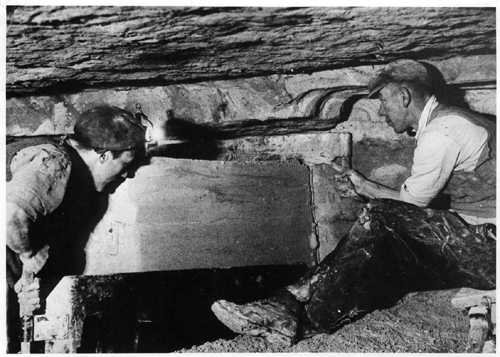

Once the two sides of the wrist stone block had been sawn, the wrist stone was removed by inserting a plug and feathers or wedges and chips between the stone and the natural bed below thus forcing the block to break down the back. Jumper or handy bars were used to bump the block out of the face or if particularly stubborn a Lewis was fitted into the face of the wrist in a narrow slot cut into block. A crane was fitted to the Lewis via a chain and the crane pulled the block out of the working face.

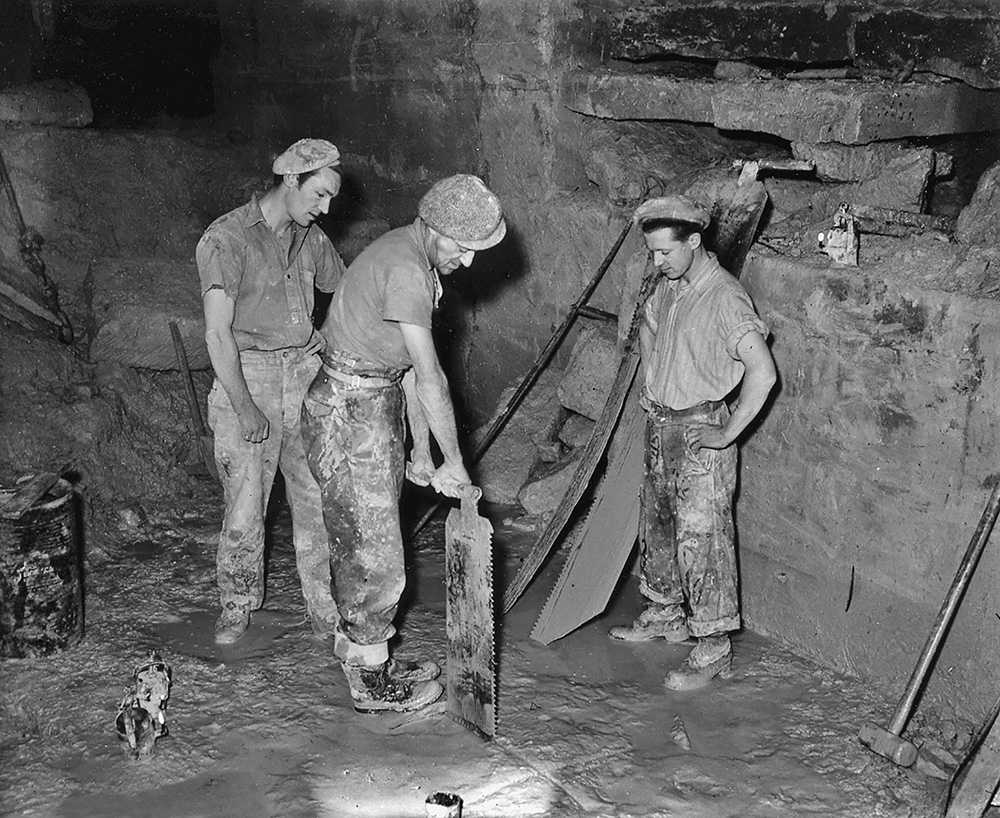

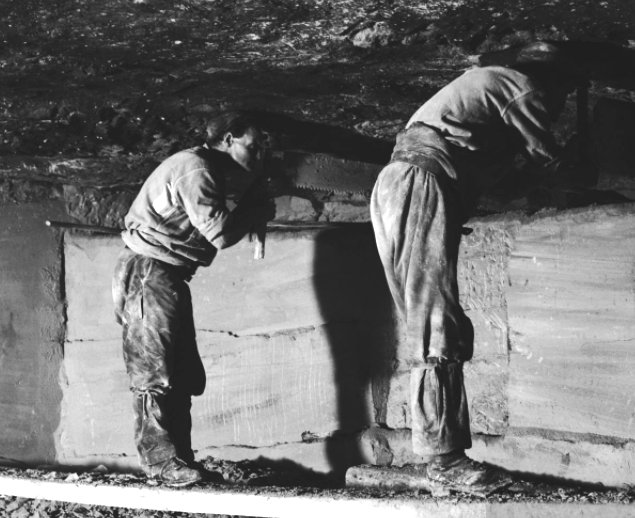

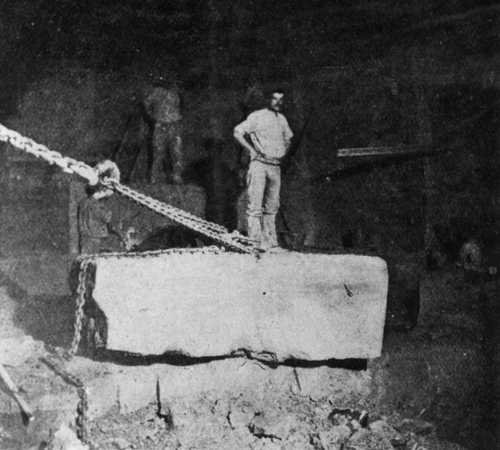

Once the wrist block was removed, the back of the wrist was cleaned with a pick to allow a sawyer with a Razzer to make a cut along the back of the remaining blocks on either side. They would also be broken from their beds by the plug and feathers and removed with a Lewis. The width of the breach and number of blocks that could be removed would depend on the quality of the stone and how much ceiling support was deemed to be needed. The last cuts called the pillar cuts either side of the breach had to be finished without stopping, or the pressure from the ceiling pushing down on the pillar could jam the saw or crack the stone. The pillar cuts on either side tended to taper towards the pillar at the bottom, this was a method used so that the sawyer could produce a larger block from the lower beds than the upper ones with less time consuming picking involved. The larger the blocks, the less cutting was needed, so the more the quarrymen could earn. This resulted in some huge blocks being produced, often weighing 6 tons or more.

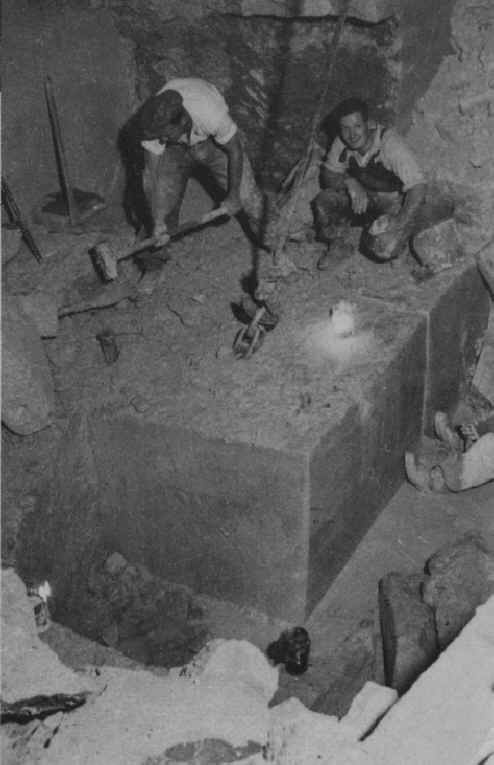

Once the top beds of stone were removed, work started on the lower blocks. They would be sawn along the back as well as horizontally and the blocks removed after breaking them off the bed with chips and wedges and a handy bar or jumper bar until the base of the workable stone was reached – often about 18 feet from floor to ceiling. The process was then repeated so the heading was driven forwards.

The stone when in the ground is classed as ‘green’ which means it is saturated with moisture. This is relatively easy to work as it is soft and cuts easily, however when it dries out on the surface it naturally becomes harder and more weather resistant. Stone quarried during the winter months needs to be protected from frosts due to the moisture content, generally, the blocks are stored underground until April, then taken to the surface storage to dry and be suitable for supplying the following winter. Today, the quarrying is much more mechanised but the same principles apply – further details can be found HERE